Series introduction

The pharmaceutical world doesn’t stand still. And neither do the intellectual property (IP) strategies that protect its most valuable assets. In this “revisited” series, we take a closer look at some of the standout drugs from our original “A to Z: Drugs in Highlight” series.

From bold lifecycle extensions to high-stakes litigation, each article will explore how IP continues to shape the destiny of these products. We will uncover the tactics, the turning points, and the lessons that matter for anyone navigating the crossroads of innovation and exclusivity in the drug discovery sector.

O is for Ozempic®: Patent thickets, formulation claims and the limits of lifecycle defence

How did Ozempic® evolve from a diabetes treatment to an intellectual property (IP) stress test?

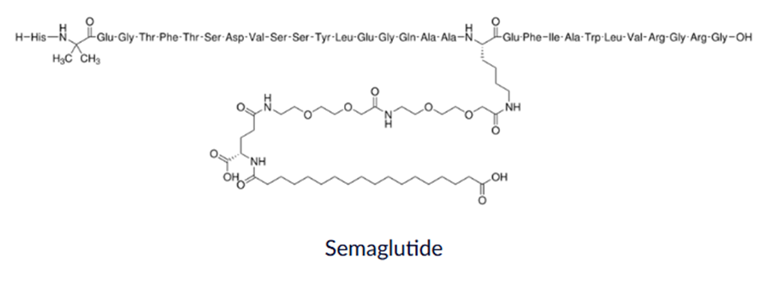

Few pharmaceutical products have achieved the commercial and cultural impact of Ozempic® (semaglutide). Originally developed as a treatment for type 2 diabetes, semaglutide (a modified version of the human hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)) has become one of the most valuable drugs in the world, driven by demand for weight management and long-term metabolic therapies. With that success has come intense scrutiny of pricing and access as well as the IP strategies underpinning continued market exclusivity.

From an IP perspective, Ozempic® represents an interesting case study in late-stage patent layering. As primary compound patents approach expiry, Novo Nordisk has relied increasingly on a dense portfolio of secondary patents covering formulations, dosing regimens, and delivery systems. This article examines how that strategy works, where it is vulnerable, and what lessons it offers for other blockbuster products entering the final phases of their patent lifecycle.

What makes Ozempic® an interesting case study in late-stage patent layering?

As with most small-molecule and peptide drugs, semaglutide’s original compound patents provided the initial foundation of exclusivity. Those patents, together with associated extensions (such as Supplementary Protection Certificates in Europe), define the baseline period during which identical active-ingredient entry by competitors is effectively blocked. However, given the scale of the commercial opportunity and the global variation in protection, patent portfolio focus has broadened from core molecule to a wider defensive perimeter.

Why are secondary patents critical in pharmaceutical lifecycle management?

While compound patent rights remain the bedrock of exclusivity in key markets for Ozempic®, attention has increasingly turned to secondary patents that will shape competitive dynamics as the core protection winds down and in jurisdictions where earlier expiries allow earlier entry. The most commercially relevant secondary patents include:

- Formulation patents, addressing stability challenges inherent in peptide drugs

- Dosing regimen patents, notably once-weekly administration

- Delivery device patents, including injection pens and administration mechanisms

Each category plays a different role in extending exclusivity. For example, formulation patents are often positioned as solutions to technical problems (e.g., degradation, aggregation or shelf-life) that were not fully resolved at the time of the original filing. Dosing patents, by contrast, seek to protect clinically advantageous regimens that improve patient compliance and outcomes. Device patents operate at yet another layer, creating barriers to entry even where a biosimilar or generic version of the active ingredient exists.

Taken together, these patents form what is commonly described as a “patent thicket”, i.e. a dense web of rights that competitors must navigate, invalidate, or design around before entering the market.

Why are late-stage pharmaceutical patents vulnerable to EPO oppositions?

While patent layering can be an effective strategy, it is also inherently fragile. Secondary patents are frequently viewed as more vulnerable to attack than core patents. For semaglutide, multiple secondary patents have faced opposition proceedings at the European Patent Office (EPO). For example:

- EP2866825 (use of long-acting GLP-1 peptides) was revoked by the EPO’s Opposition Division. This decision was later upheld by the EPO’s Board of Appeal.

- The EPO’s Opposition Division rejected the opposition against EP3870213 (stable semaglutide compositions). This decision has been appealed by the Opponent.

These types of challenges often focus on whether the claimed inventions represent genuine technical advances or merely routine optimisation of known parameters (such as concentration, excipients, or dosing intervals).

For opponents, the logic behind such challenges is simple. Even partial wins such as narrowing claims can weaken the “patent thicket” and speed up market entry. For patentees, the challenge is to defend each patent on its technical merits while maintaining consistency across the portfolio.

How does the Unified Patent Court (UPC) impact patent portfolios and exclusivity?

The introduction of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) adds a new and potentially destabilising dimension to the secondary patent landscape. Historically, disputes over patents were handled piecemeal across national courts allowing patentees to absorb losses in some jurisdictions while maintaining protection in others. Under the UPC, a single proceeding can address infringement and/or revocation across participating member states, concentrating both opportunity and risk in one forum.

In 2023, the EPO granted Novo Nordisk’s request for unitary effect for EP3870213. Unitary effect effectively turns a granted European patent into a “unitary patent”, giving it uniform legal status across participating member states. This approach offers significant advantages for cross-border enforcement, allowing Novo Nordisk to bring a single infringement proceeding before the UPC that covers the entire UPC territory (currently 18 EU member states). At the same time, it comes with risk. Any central revocation decision at the UPC will invalidate the patent across all UPC territories. This interconnectedness underscores the importance of having robust, technically sound claims that can endure scrutiny at the UPC.

For patent portfolios like semaglutide’s, this raises a critical question for patentees: which patents are strong enough to survive centralised scrutiny? From recent EPO and UPC case law, there is a growing sense that not all layers in a “patent thicket” are equal. Some are designed primarily as negotiation tools or speed bumps rather than as litigation-ready rights. The UPC forces patentees to confront that reality more directly and could prompt a more selective approach to enforcement.

Is patent layering a strategic necessity in pharma?

Patent layering in high-value therapeutic areas is often used to strengthen market exclusivity. These strategies can extend protection beyond the primary compound, creating a layered approach to IP management. From a legal perspective, the focus should be on substance. Secondary patents that solve genuine technical challenges and are backed by credible data remain defensible. Those that do not are increasingly vulnerable to invalidation through EPO opposition, national revocation, or UPC proceedings.

The Ozempic® (semaglutide) patent portfolio illustrates both sides of this dynamic. It demonstrates how layered protection can sustain exclusivity well beyond the life of the compound patent, while also showing how exposed that protection becomes as the portfolio matures.

What lessons does Ozempic® offer for future blockbuster drug patent strategies?

Strong exclusivity in high-value therapeutic areas rarely depends on a single patent. Portfolios like Ozempic® (semaglutide) patent portfolio show that long-term protection comes from a structured, multi-layered approach built over time. Success depends less on filing volume and more on filing patents that are timely, technically robust and supported by solid evidence. Some key takeaways for future blockbuster drug patent strategies, include:

- Start early with strong secondary patents. Secondary protection should not be an afterthought bolted on late in development. Strong portfolios are seeded early with claims that address concrete technical challenges, such as stability, delivery, dosing regimens, and manufacturing efficiencies.

- Back formulation and dosing claims with solid evidence. Formulation and dosing regimen claims can succeed or fail on their evidential footing. The standard is moving toward credible, reproducible support at filing.

- Plan for UPC risk through proactive portfolio planning. The risk of central revocation under the UPC means portfolios need structured, forward-looking planning. One strategy could be to identify core patents that are critical to maintaining exclusivity and surround them with supporting patents that can be amended or surrendered without weakening the overall position.

- Use settlements strategically to protect value. Litigation can clarify boundaries, but risks eroding portfolio strength if the wrong patent is tested. Settling early can preserve commercial certainty, prevent damaging precedent, and keep the focus on overall portfolio objectives rather than isolated wins.

What does Ozempic® reveal about the future of pharmaceutical lifecycle defense?

Ozempic® shows that a well-engineered patent portfolio can still deliver significant commercial advantage. Such patent portfolios can extend exclusivity, support negotiating leverage and buy time for lifecycle innovation. But the patent landscape is evolving. As UPC case law develops and scrutiny of secondary patents intensifies, it will be critical for companies planning the next generation of blockbuster drugs to build patent portfolios with robust, defensible layers. Patent portfolios that endure will be those anchored on genuine technical contribution, aligned with clinical and regulatory milestones, and supported by credible data.

To discuss how these developments may affect your patent portfolio or upcoming filings, contact our team today.